SYNECDOCHE, NEW YORK (2008) - Mauvaise Foi and Parallel Realities

syn·ec·do·che

səˈnekdəkē/

noun

a figure of speech in which a part is made to represent the whole or vice versa

What is reality?

This question is the basis of almost all philosophical thought since homo-sapiens could stack rocks, and yet somehow we’re no closer to objectively answering it. Clearly, within our human relationships, we find ways of communicating our experience to others. We use language, like I’m using right now. From there we create adjectives to say, “Red is red and blue is blue.” But for this discussion let’s just shed ourselves of the burden of this particular sense of, “reality.”

In fact, when we discuss reality on a daily basis, we very rarely dispute the color of an apple, or the solidity of a rock. What we often discuss is the way the world is. Virtually every day we discuss and argue with people that do not understand the way the world is. And every day we see the consequences of ignoring the power that those subjective realities hold. Be it religiously motivated terrorism, or the hatred created from years of repetitious radical racism, subjective reality is easily observable as a powerful and ever-present force.

“Well, that’s psychosis. Subjective reality isn’t reality.” All that we can truly verify, is our own reality.

Descartes’ famous quote illuminates this limit of human perspective: “I think, therefore I am.”

Within that reality, we are free to pursue happiness, but that subjective sense of reality has always had more power than we might attribute it.

Perhaps you’ve heard someone say, “You create your own happiness.” What is that but choosing to adjust the way we see the world, for our own sake. And if we’re able to truly adjust our perspective on the world, are we not changing the nature of the world itself? At this very moment your world is constructed not of just objective truths or experiences, but of amorphous, impressionable perspectives. Whether those perspectives are, “right” or, “wrong”, we are living through them.

For many, these perspectives are built up over years—they don’t just appear one day (like the absurd to Camus). They develop deep within our subconscious and then we unknowingly project them onto the world. The way we view the world is directly correlated to who we are, and how we see ourselves.

I think the difficulty of Synecdoche, New York lies in a different realm than most people (including myself) are used to delving into. It’s emotions are somewhat accessible, but the way it’s told and the pathways and back alleys we have to meander to find a greater understanding of these characters is what defines it. Charlie Kaufman is infamous for creating worlds like this, where we lose track of timelines, where other people seem strange and confusing and where life in general has a supernatural and absurd quality.

And yet… Are these not the qualities of every day crises?

My inability to immediately grasp Synecdoche, New York isn’t due to difficult narrative (though Synecdoche, NY does require audience participation), it was a failure of establishing a mutual vocabulary between the film and my ability to digest it. And so as understanding is gained, and as we see these moments for what they (probably) are, the film blooms in unexpected ways—and this is the beauty of Synecdoche, New York and it’s relation to the viewer. Synecdoche, New York is like life. It’s dirty and seemingly incomprehensible, and then some moments (almost exclusively in retrospect) we realize and actualize.

The film opens, and immediately establishes several details. For many watching this scene, they may not realize that it takes place over five weeks, but understanding this is essential to understanding Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman).

Caden lies in bed, the radio is on and the talk-show host says it’s September 22nd. He goes outside, collects the mail and when he comes back inside, the radio says it’s October 15th. Then the paper says October 17th. Caden smells milk in the fridge and says it’s expired, yet, the carton says it expires on October 20th. The radio host then says, “Happy Halloween, Schenectady.” And finally, the paper reads November 2nd.

In a matter of minutes, we propel through over a month of life and hardly know it. This illustrates a powerful crisis in human life, that is, life just passing us by without our even feeing it. The mundanity of the every day routine lulls us into a simultaneously comatose and active participant in our own lives.

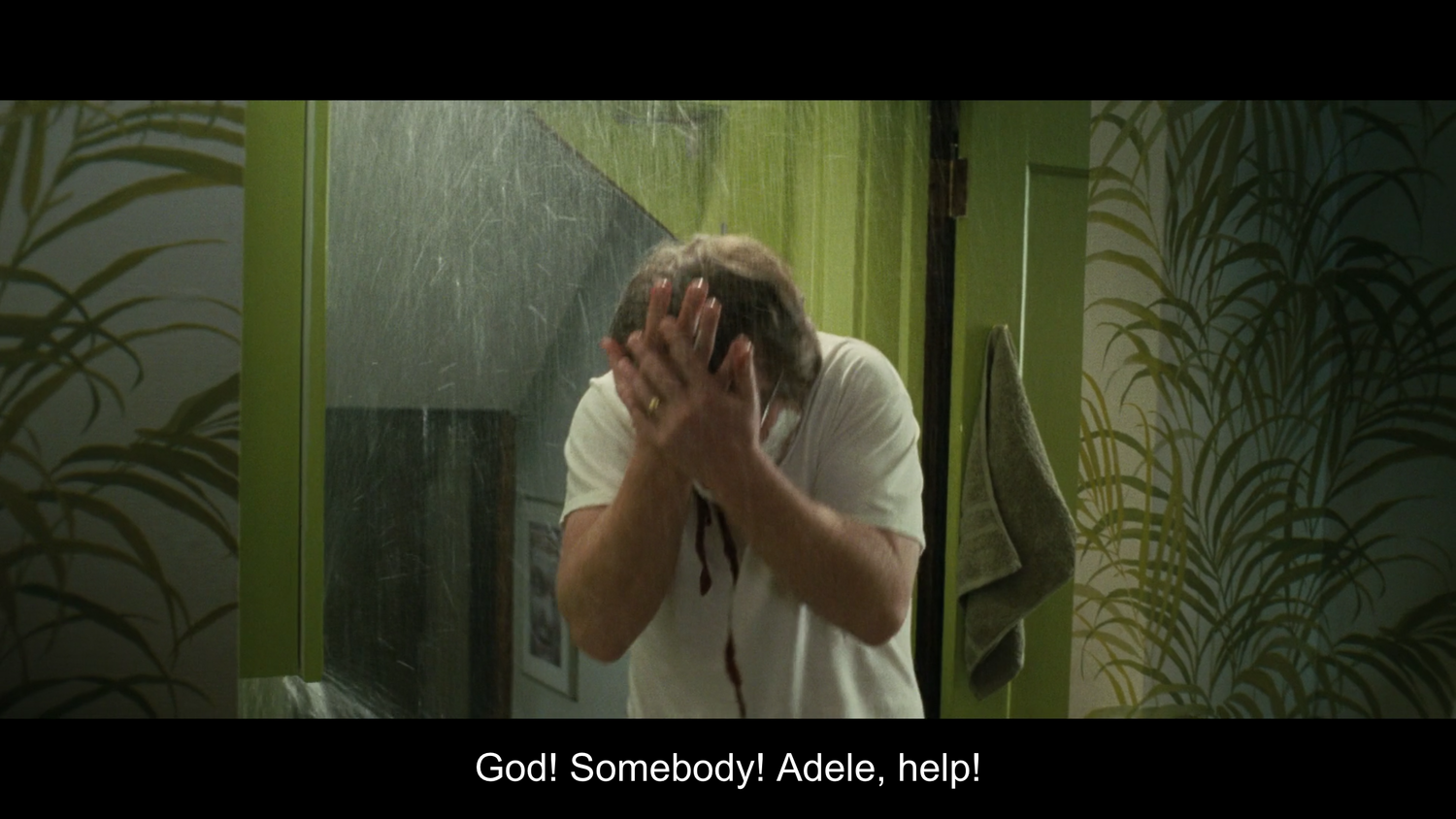

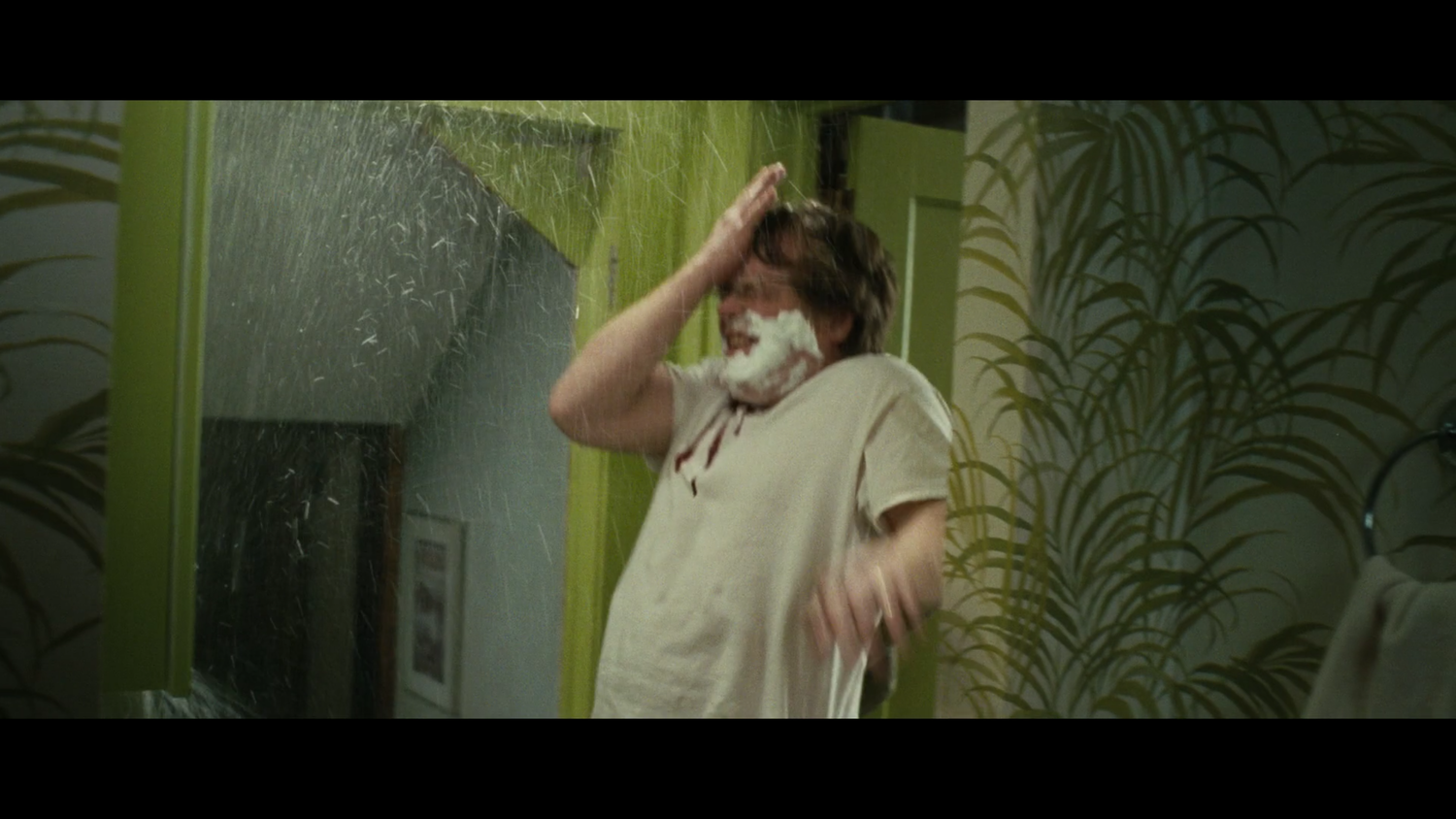

Dramatically, or perhaps comedically, in the next scene, the sink, the object he uses every single day explodes up, striking Caden in the forehead. Blood is everywhere, and he cries for help.

“God! Somebody! Adele, help!”

This, among many other things is the catalyst for Synecdoche, New York’s driving theme, and Caden’s internal (and external) crisis. The sink, the object that punctuates the beginning of each routine day for Caden, is the object that sparks his growing sense of the looming presence of death. Caden is dying, and will be dying.

Throughout the entirety of Synecdoche, New York, we follow the story of Caden Cotard, but this presents immense issues. Caden is an incredibly unreliable narrator. We see the world through his eyes, yet as the film continues, a very strange and confusing disconnect with reality appears. And because of that perspective, patterns emerge that tell us about what’s really going on in Caden’s mind.

Death becomes an inescapable theme of Caden’s life. Or more specifically, and more accurately, dying becomes the theme. There’s a critical distinction within that slight change.

Caden’s external reality is a reflection of his internal perspective. When he realizes he’s growing older and that time is running out, externally we see a self-perpetuating cycle of atrophy. As Caden ages he’s confronted with new and increasingly obscure medical issues. He’s shuffled from doctor to doctor, popping pills, undergoing operations and generally living at will to his physical deterioration. And yet, Caden doesn’t die. In fact, he lives what seems to be a long life.

When Caden is smacked in the face by his faucet while shaving his face—a process he completes every day of his life—he sees how non-existence and death frames his life. But this isn’t a eureka moment. It’s the start of a slow agonizing walk down an endless circular staircase.

“This is the start of something awful.”

Caden's wife (Catherine Keener) sees his play and criticizes him for his lack of ambition. “But what are you leaving behind? You act as if you have forever to figure it out.”

We cut to the television, presumably the next morning. A cartoon is playing. The narrator says, “When you’re dead, there’s no time.”

Adele, Caden’s wife tells their therapist in a couples therapy session, “I’ve fantasized about Caden dying. Being able to start again, guilt-free. I know that’s—That’s bad.”

Caden Cotard is a local theater director and he’s directing a production of Death of a Salesman. A particular detail of his production is that he cast young actors in the roles of Willy and Linda Loman—during a break he offers a bit of character advice to the actor portraying Willy.

“Try to keep in mind that a young person playing Willy Loman thinks he’s only pretending to be at the end of a life full of despair. But the tragedy is that we know that you, the young actor, will end up in this very place of desolation.”

The actor responds, “Okay.” Then gesticulates awkwardly, unable to understand how to portray that.

Caden receives the MacArthur Grant to pursue something great within his artform. His idea is to create a massive theater piece. “Something true.” “Something real.”

He tells his cast, “ We’re all hurtling towards death, yet here we are for the moment alive, each of us knowing we’re going to die. Each of us secretly believing we won’t.”

Claire (Michelle Williams), his actress and later his wife responds, “It’s brilliant. It’s everything.”

The world around Caden quickly begins to decay. The hospital’s become darker, dirty; almost out of a horror film. The neighborhood around his massive theater becomes riddled with homelessness and despair. He learns (or perhaps imagines) that his daughter is fully tattooed, and a famous stripper. His Father dies. And whether true or untrue, Caden fabricated a narrative that demonstrates what he wants to believe. The world is dying.

The tragedy of Caden’s character is that his fixation on death and the atrophy of the world seeks only to blind him from the truth that he seeks. The further he delves into reality, the more he just dives deeper and deeper into his own fatalistic perspective. He begins to write notes to each of his actors, describing a horrible thing, meant to inspire a performance.

But just as Caden tries so desperately to capture the essence of human life, he constantly places a perspective on it. Saying that this is or isn’t true. He calls a display of happiness a lie—he walls it off blocking it from view. And as his reality becomes so rigid as to not accept the possibility of happiness, the world becomes strange to him.

But it goes further than that. Caden’s inability to see life as anything other than the act of dying throws every day interaction into severe contrast. One of the most basic acts of life, walking, becomes something of sharp interrogation. It doesn’t feel right. To Caden, even this seems false, and a lie.

Caden passes a man walking inside the set of his play. He tells the man, “People don’t walk like that.”

The man replies, “What? Too…?”

“No, just walk like yourself.”

“Watch. Watch this.” The man tries to walk again. Caden walks away, unable to help the man. The man tries again. “Watch this.”

Each effort appearing more and more unnatural.

“Well, there are two kinds of psychosis. They’re spelled differently. P-S-Y is like if you’re crazy, like Mama. S-Y is like these ugly things on my face.”

His daughter responds, “You could have both, though.”

Caden Cotard isn’t so different from us as we might think. Synecdoche, New York packages it’s crisis in ways that allow us to conveniently write off his struggle as something manufactured out of psychosis. But reality, regardless of who’s perspective it is, is so much dirtier. The human ego is often unable to distinguish itself from the outside world. For us, it’s not psychosis. It’s just seeing what we want to see. Or focusing on what we want to focus on.

We so desperately want to see ourselves as dynamic individuals capable of transcending our own problems and struggles. Of learning and understanding ourselves and the world enough to move forward towards the idealized version of ourselves. But more often than not we are made fools by our past and slowly, we become who we are, not who we are going to be. And as this happens, the world and the possibilities it presents grow smaller, and smaller. And we become rigid representations of our own fears and perspectives. Or as Sartre would say, we become representations of our pre-reflective mind.

In my last post on Toy Story (which I encourage you to read, if you haven't yet), I discussed Facticity versus Transcendence. That is, the difference between who we are and how we view ourselves—a concept created by the existentialist, Jean-Paul Sartre. But Sartre and his longtime partner Simone De Beauvoir created another concept that perhaps illustrates Cotard’s disconnect better than any. In the original French this is, Mauvaise foi. In English it’s called, bad faith.

Bad faith is characterized by self-deception—but further, it’s self-deception about our own lives. That is, that we are presented with a variety of choices about how we choose to live, yet we lie to ourselves and say that we have no choice. That we are irrevocably tied to the way things are. Most dramatically, Sartre would say that many people live in fear of an imagined world. One that we construct to make ourselves more comfortable with our own decisions.

Yet this comfort is short-lived and slowly as the world changes around us in reaction to our decisions, we’re confronted with the reality that we our lives are a culmination of these decisions.

Olive, Caden’s daughter, is watching a cartoon. The narrator says, “There’s something at play under the surface, growing like an invisible virus of thought. But you’re being changed by it.”

Unintentionally, Caden Cotard constructs a world around him of imagined fears, paranoia and death. He sees death in himself, and the darkness in the world. From our vantage point, we say that this is not reality and we view him as an unreliable narrator. But would we not view ourselves in a similar way if we had a bird’s eye view of our life? Would we not see that we convince ourselves of fears and truths that turn out to be nothing more than briefly illuminated wisps of smoke?

And what of our own reality, then? If every day we’re at the mercy of our own pre-reflective conscious, how can we call what we experience objective? If we are constantly working to undermine our own freedom by walling up what we wish to not see, how can we claim to have a holistic perspective on… anything?

I think for most of us, it’s difficult to reckon with the limits of our own self-importance. We look at ourselves, and we see the world, because for us, we are truly all that we have. The people that surround us inhabit our minds in ways that may not be entirely accurate. And as we make judgments about the nature of those people, we make judgements about the nature of reality.

Are we good? Are we bad? Are we living or are we dying? But these are questions without answers. They’re questions that freeze us in our tracks. And what’s important to remember is that truth in this sense, does not exist. When we feel the weight of existential crisis on our shoulders, our first reaction is to say, “this is the way humanity is.” But that is not reality. It’s one reality, but it’s not reality.

We’re just one of an infinite number of perspectives that simultaneously inhabit one physical world. And so to make assertions about that nature of humanity sends us spiraling into the darkness of our own confusion. The challenge is to see that just as there is death, there is also life. Death and life, existing simultaneously. Billions of realities, but also just one. Humans existing in an infinite number of parallel universes, intersecting for seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, years or decades, But never as tight as we may wish. Where timeline’s don’t exist—just moments.

The sunrise plains are a tender haze

And the sunset seas are gray,

But I stand here, where the bright skies blaze

Over me and the big today.

What good to me is a vague 'maybe'

Or a mournful 'might have been,'

For the sun wheels swift from morn to morn

And the world began when I was born

And the world is mine to win.

In 1947, Badger Clark wrote, The Westerner and it illustrates a concept that’s key to understanding Synecdoche, New York. It’s truth is somewhat troubling. No matter how empathetic and sympathetic we may be, our individual realities are composed of our often flawed views of the outside world. And so, if we are actively constructing an outside world through our subjective reality, our flawed perspectives and mauvaise foi, we are creating the world in which we live. Not merely experiencing it.

And so to an individual human, the fear of death is not necessarily the fear of your place at the Thanksgiving table being vacant. It’s that, with your passing, the world also passes. That with your demise, the world ends, as well. As you die, so does everyone you know or ever knew.

As Caden finds himself on the brink of death, he exits his home and finds that the world around him is dead. Dead bodies litter the streets and he silently walks by them like a ghost. A voice calls to him.

“What was once before you, an exciting and mysterious future is now behind you. Lived, understood, disappointing. You realize you are not special. You are struggling into existence, and are now slipping silently out of it. This is everyone’s experience. Every single one. The specifics hardly matter. Everyone is everyone. So you are Adele, Hazel, Claire, Olive.”

The difficult, dark beauty of Synecdoche, New York isn’t that we have to accept that there are billions of individual realities all existing at once. It’s that in every infinitesimal moment of our lives we must take responsibility for ours.

“Whoever has no house now, will never have one. Whoever is alone, will stay alone. Will sit, read, write long letters through the evening and wander the boulevards up and down, restlessly while the dry leaves are blowing.”

“Goodness, that’s harsh isn’t it?”

“Well, perhaps. But truthful.”

Bret Hoy is the creator and co-editor of Monolith Medium, an award-winning filmmaker, and writer.