Aristotle dedicated his life to the pursuit of scientific, quantifiable truth. Originally a biologist, he focused his attentions on the classification of plant and animal life—looking for some structure in the undefined studies of the ancient world. When classifying animals he would take the best, healthiest example of a species, and then from that vantage point start to deviate, finding the many different mutations and deviations. This calculated method of sorting and separating all life isn’t a strategy that he relegated exclusively to biology. In 350 BC, Aristotle took this decidedly objective approach and applied it to the humanity.

In his preeminent work, the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle makes his strongest argument for the purpose of human life. To make sense of such a gargantuan task, in Chapter Seven of Book One he likens human purpose to medicine, strategy, and architecture.

“In medicine this is health, in strategy victory, in architecture a house, in any other sphere something else, and in every action and pursuit the end;”

In other words, humans live their lives in pursuit of happiness, whatever that may be. While the actions are diverse (sexual pleasure, wealth, or honor) the ends are the same. That is happiness pursued for no end other than itself. But how animals function on instinct, that is, an inherent biological imperative to achieve an end, humans must develop themselves to achieve the end of happiness. To make decisions based on gained knowledge on how to live each day. Aristotle calls this action, Rationality. Rationality in it’s widest sense being the ability of a human to use logic or reason.

Aristotle

What Aristotle seemed to be digging at what is an internal drive, a sense of defining who you are as a person, by the action you take to an end, but he stops well short of that. Limiting himself to coldly and scientifically defining humanity’s purpose without muddying the waters with more difficult and specific ethical questions. But this seems only prudent for a philosopher who defines humans as a conscious being that pursues happiness. How could he reconcile the slavery or demoralizing misogyny of his era with his theory that a human is only truly human when they’re able to pursue their own brand of happiness?

However, for a human to fully devote themselves to this pursuit they must be free to act. They must be liberated. And to be liberated is to be given license to choose— and to choose is to be conscious.

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy is fairly up front with it’s intent. The films utilize the three colors found on the Tri-Color Cockade popularized by sympathizers of the French Revolution in the late Eighteenth Century. However, the first in the series, and the subject that I’m focusing on today, "Blue" is not so salient as the color might imply. The color Blue in this case symbolizing, “Liberty.” And indeed the film begins with a liberating scene, but not as you might imagine. And in fact, I think it's important at this point to recognize our romanticized and distorted view of, "revolution" and, "liberty."

As an American, my idea of Liberty has been shaped by events that have come before me. The American Revolution being the foremost event that shaped post-Enlightenment politics. Because of that I associate Liberty with it’s purely positive elements. Freedom from the tyranny of a cold Monarchical government. The freedom to do as our nation chooses. And indeed, the United States wasn’t the only society to benefit from Enlightenment thought.

In the late Eighteenth Century, the French Revolution shook the foundation of what Europe took for granted as, “Order.” Peasants up-ended their Lord’s nobility and claimed the power that was originally granted only to Kings. The power to decide how their country would look and be governed. It was an age where the status quo was questioned, and brought to its knees. One where the common man and his family triumphed over elites. Where a country chose who it was going to be and forgot who it was.

In 1775, King Louis XVI was consecrated into The Crown at the Cathedral in Reims, France. During the ceremony, the young twenty year old was anointed with Holy Oils passed down over centuries. These oils were contained in a vial called the Holy Ampulla. The ceremony indicated that Louis XVI was not just an ordinary man, he was a man ordained by God to govern the Catholic nation of France. This meant his nobility could not be questioned.

Less than twenty years later, in 1793, Phillipe Ruhl, a common man, blacksmith, and a French Revolutionary stormed the Cathedral, seized the Holy Ampulla and with his blacksmith’s hammer, the hammer of a commoner he smashed the vial on the pedestal of a statue to Louis XVI. Holy Oils splattered across the floor of the Cathedral.

Before the catastrophic, deadly crash of the car that defines the beginning of Three Colors: Blue, Kieslowski foreshadows the family's demise—the car is leaking oil.

The young girl who we never meet elsewhere watches out the back of the car as distorted images of cars weave in and out behind them. She doesn’t look forward—She watches what’s behind her intently.

The car glides through the fog of the country side, and past a young boy playing a ball and stick game. The car careens into a tree, and all goes silent.

In the crash, Julie Vignon de Courcy loses her Husband and Daughter simultaneously. She is the sole survivor, alone. Thus we’re introduced to Kieslowski’s version of Liberty. Merriam-Webster’s definition: “the power or scope to act as one pleases.”

“Do people really want liberty, equality, fraternity? Is it not some manner of speaking?” - Krzysztof Kieslowski

Krzysztof Kieslowski

Kieslowski’s focus is on what’s lost when we gain freedom. To be free is to shed yourself of what once shackled you, of order, to gain the ability to choose for yourself. My American mind wants desperately to delineate this as a positive thing. As something that is inherently good for humans. But Kieslowski indicates that this is not necessarily so—that the absence of order is chaos.

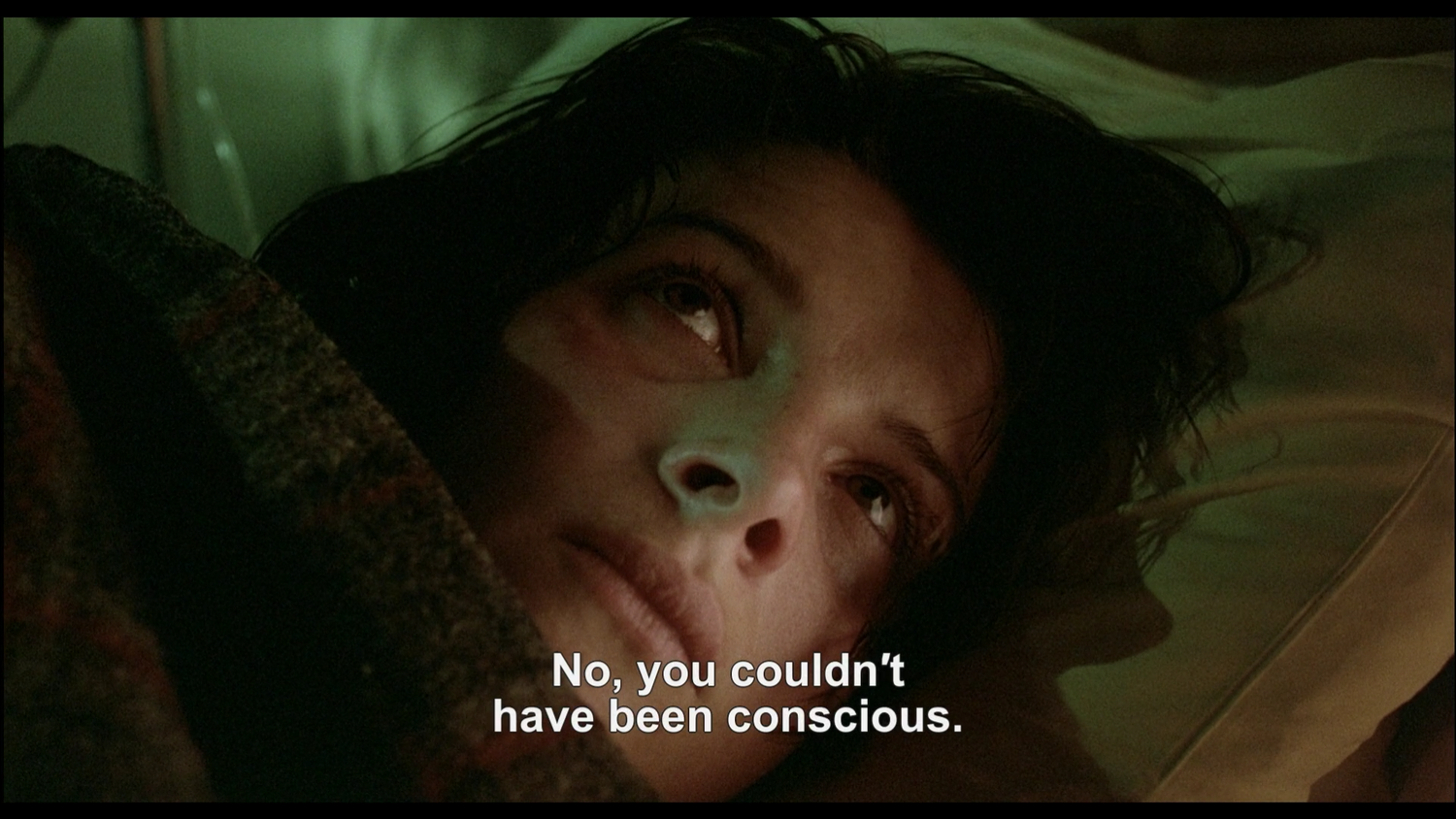

After hearing of her family’s death, and that she is left to live alone, she smashes a window as a distraction to steal pills to kill herself. She is unable to go through with it. Back in her hospital bed, her husband’s collaborator and friend, Olivier brings her a portable television. He shows her a clip of a sky-diver, jumping out of a plane, plunging to earth in a complete free-fall.

Later, Julie watches her famous husband’s funeral on the television. Kieslowski takes us in incredibly close to the corner of Julie’s mouth. It flickers almost as smile, then tears fall as the deep, deep sadness sits in. This play between freedom and death—between order and chaos—between happiness and aimlessness is at the heart of what makes Blue a compelling and rich film on many levels.

While Julie’s journey after she’s left without her husband and daughter are compelling, her decisions echo on a philosophical level. The painful relationship to the memories of the past send her into a crisis of identity and the extremity of her choices confuse those around her.

Julie lived a life of luxury before the crash; one provided by her husband's status as an acclaimed composer and director. Her name itself, with the addition of the, "de" hints toward the elite nature of the family. One that lives in a beautiful stone mansion with gardeners and maids. It's hard to view the relics of Julie's pre-crash life without visualizing the substantial privilege. A throwback to the life of a Lord in feudal France.

But this is not who Julie wants to be. Her main goals when coming home are of change. She requests that the Gardener empty out the, "Blue Room." While he says how deeply sorry he is for her loss, she is unaffected.

She enters the kitchen and hears her maid crying in the pantry and approaches her.

“Why are you crying” Julie asks.

“Because you’re not. I keep thinking about them and I remember everything.” The Maid says.

This identity crisis comes full-circle when Julie visits her mother. She’s living in a home where she’s cared for by nurses, but is clearly suffering from Alzheimers.

Upon seeing Julie she says, “They told me you died. You seem fine.”

But later in the conversation she asks Julie if she had anything new to tell her about Julie’s husband and daughter. Julie replies, “My husband and daughter are dead.”

The mother says, “Yes, they told me.”

While the Mother is clearly speaking to Julie, she believes she's talking to her dead sister, Marie, but visually the effect is infinitely more complicated.

On the television, a pair of feet shuffle to the edge of a platform. An aged old man is tethered to a bungie cord. A pair of young men, urging him to jump off. The old man almost doesn’t go. He’s fighting it, but is pushed over the edge. He falls hundreds of feet.

When Julie wasn’t able to kill herself she became someone else. Someone with a different life, who makes different choices. The mother unknowingly reveals this to Julie in that moment.

Julie says, “You know, I was happy before. I loved them and they loved me.”

A skydiver jumps out of a helicopter, loosely connected via an umbilical cord-like bungie. His arms flailing as he falls to the earth. The cord is so long, the man falls for quite a long time.

She tells her mother, “I want no possessions, no memories… no friends, no lovers—they are all traps.”

Her mother warns, “One can’t give up everything.”

Yet we see Julie try to give up everything she has. She indicates to her estate lawyer that she wants to liquidate all of their possessions including their sizable home (maybe: 1789 Abolition of Feudalism) and she chooses to live in a secluded apartment. But as much as she tries her best to eliminate any memories of the past, we see that there’s no way to disconnect herself.

The young boy who witnessed the crash contacts her and they meet up. He says that he has something of hers. Once they meet, he shows her a Christian Cross necklace. It had flown off in the accident, and he found it, but wanted to return it. Instead of taking it, she tells him to keep it.

After a documentary on her husband airs, she learns that he had a mistress. Julie finds the mistress and confronts her. She learns that she’s pregnant with her dead husband’s child. The mistress clutches a cross around her neck. Julie ends up giving her and her husband's unborn child her home instead of selling it.

The Mistress, clutching her cross

Both characters are signals to a past that Julie has tried to distance herself from. But she is clearly unable, or unwilling to cut her ties fully. Her past indirectly fuels the future she creates.

Much like the abolition of feudalism, the French Enlightenment writers such as Voltaire (see: Sorrentino v Voltaire) wanted France to reject the Catholic church as an empowered government organization. During the Revolution, this came to fruition and the National Assembly relieved the Catholic Church of its economic and governing power in France, but simultaneously, gave religious freedom a home. Protestants could practice publicly, and Jews were given citizenship. Massive breaks in convention from Eighteenth Century politics.

However, throughout the revolution, until the conflict reached a boiling point, the French citizens were convinced that Louis the XVI was great. Enough so that while abolishing feudalism, they still believed in the sanctity of the Crown. It’s a question that lingers on my mind whenever I consider this era. Why were they so confident in Louis' divine rule? While they eventually overthrew and killed him and the Queen Marie Antoinette, this willing nature, the nature to believe in a centralized figure gave way to Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise to power, and eventually, allowed him to become Emperor.

The French people carried their deep-seated beliefs about structure and order while trying to up-end Western Politics, and because of that they were unable to fully shed themselves of their past. Nostalgically looking through distorted glass into their past exactly like Julie’s daughter, staring out the back window of the car. Unable to relinquish it, with a distinct brand of masochistic sentimentality.

While Julie lives in her new apartment building, she meets a prostitute that’s sleeping with one of her neighbors. Lucille. Because Julie stands up for her and refuses to vote with the other neighbors to kick her out of the building, Lucille finds Julie to thank her and becomes attached in an unique way. Her attachment goes so far as her calling Julie in the middle of the night, in a moment crisis. Julie goes to the strip club/brothel where she works. Lucille is crying and explains what happened.

“After I changed, I came in here for a drink. I looked around the audience for no reason. Right there… in the first row, I saw my father. He looked tired… almost nodding off. But he kept staring at the girl’s ass.”Seeing her father in this environment was so distressing that she called on the only person she knew. Julie, trying to make sense of why she would put herself in this situation—why continue to stay in the brothel and work while her father could show up any night?

Julie asks, “why do you do this?”She responds, “Because I like to.”

When Aristotle defined humanity, he did not have the sense of the freedom that we experience today. In fact, our sense of what freedom is, that is, freedom of thought, external and internal, is one that would be entirely new to him.

This internal freedom is one defined in it’s earliest sense by stoic philosophers. While you are limited in the external sense, your mind is your land. You could be in shackles, yet your mind is free to think as you like. Each human has to choose between your own compulsions and the compulsions of the law. But freedom, and the journey following is just a start.

In his book Confessions, St. Augustine writes, “Freedom from crime, is only the beginning of freedom.”

That is, when you are free from the compulsions of the law. When you are free to act as you please, to pursue your own happiness, you’ve just begun to define freedom. And in fact, our definitions of freedom are still evolving. Secularism and Feminism are major themes of Blue and identify areas of our life from which many of us are still in shackles.

Kieslowski takes this to the next logical step. Three Colors: Blue makes a strong case to say that true freedom does not exist. While Julie is free from her marital bounds and from the obligations of her family, it incessantly haunts her.

She sleeps with her husband’s friend Olivier, and the next morning unceremoniously leaves. She brutally scrapes her hand along the stone wall surrounding her mansion. The marriage over, her husband dead, yet the guilt and the obligation remain. Enough for her to externalize her burdens.

She finds one of her daughter’s blue candies, and manically crunches on it until she’s consumed it entirely; throwing the wrapper into the fire.

She finds the sheet music for her husband’s final, yet uncompleted piece of music and throws them into a trash truck, watching the machine crush it until she knows it’s gone.

The irony is that while Julie articulates a desire to never remember and to leave behind her past life, she gives it a home and holds a special place for it. She nostalgically looks back on what once was, and who she was. Going so far as completing her husband’s piece, and allowing it to be performed. She’s allowed love, hope, faith and beauty to live on.

Yet as she considers all of this, at the end of the film, we see an eye in extreme close-up. In the eye there is a reflection of a woman, naked and curled up in the fetal position. Then we cut to a wider shot of Julie as she gazes directly forward at the naked and pitiful human. Tears roll down her face, and blue creeps up into the frame.

The corner of her lip turns up into a slight smile.

Commoners storming the Bastille.

During the French Revolution in 1790, revolutionaries in the National Assembly were creating government from scratch. Because France had no original structure outside of Feudal Lordship, the sections of the country were split in ways that didn’t suit themselves for equal representation. In fact each province was so different that sometimes there were linguistic differences between Southwest Franc’s and Urban Franc’s. Enough so that subtleties of languages turned into different dialects, each representative of a distinct culture.

This divided France couldn’t do. In the revolutionary’s minds, to create a new system of government, they needed a clear and precise idea of what it meant to be French. Because of this, the Deputies of the National Assembly sought to create new regional lines. Ones where elected representatives could help govern their constituents. But by tearing down these regional delineations, they were infringing on centuries of culture. The Assembly felt it necessary to come to an agreement on a national language. While, France choosing French as the, “National Language” might seem trivial, a French, Catalon-speaking objector wrote.

“To destroy the Catalon language, it would be necessary to destroy the sun, the cool of evening, the type of food, the quality of water, in the end, the whole person.”

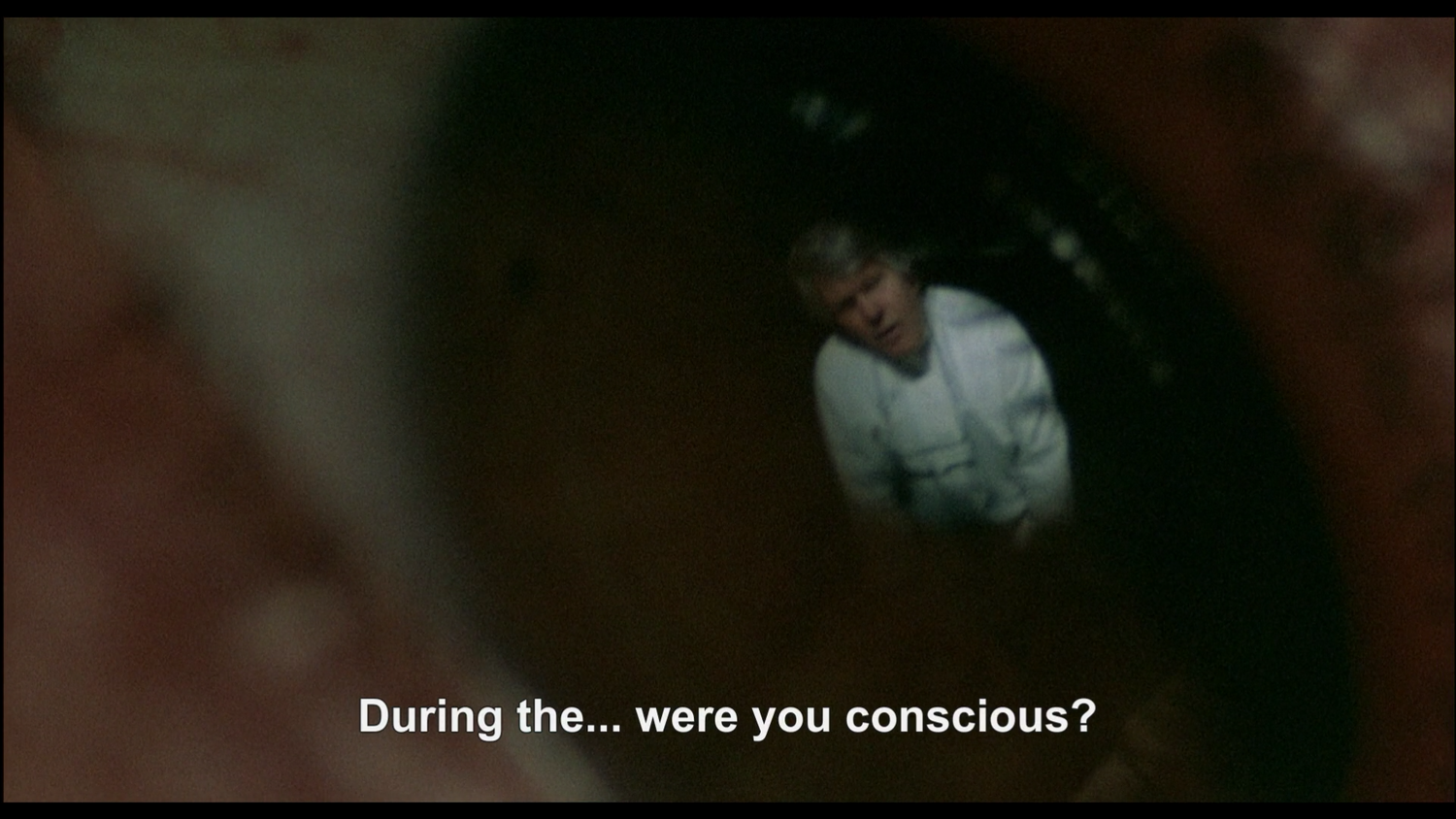

Julie peers through the circular window of a courtroom. A trial is in session. While we get no glimpse, or context of the trial itself, we hear these particularly powerful words.

“Where’s the equality here? Is the fact that I don’t speak French any reason to refuse to hear my side?”

Bret Hoy is the creator and co-editor of Monolith Medium, an award-winning filmmaker, and writer.